A rough hundred miles south of Georgia, and roughly ten miles west of the Flagler Beach Fishing Pier, where Spanish mackerel, bluefish and snook are yanked wriggling from the Atlantic Ocean, a woman in a motorized wheelchair feeds a pig. The pig is her friend, her buddy, her good luck charm. She loves his sounds, the whiskers that grow from his lovesome snout and the intelligent eyes. Her pig does not speak English, but what matter? His language of squeals and wiggles, of nudges and wags is all he needs. When he sees Lory appear in the morning with her bucket, he tromps over, a plump black zeppelin on tiny legs chuck-full of personality. “Here you go,” Lory says, and throws a handful of pellets into the mud. Lory also feeds this fine boy’s sister, that sister’s sister and their cousins and brothers and parents, grandparents and friends. As soon as the pigs in the yard catch on that Lory has arrived, they stomp in from all parts of the farm, a splashing grunting wiggling leaping stampede to the sound of crowing roosters and barking dogs.

Lory started with just the one pig, a gift from her sister during the time when she still was getting used to the chair and her new life as what people called a quadriplegic. Somehow that one little pig multiplied into two pigs, and then there were three pigs. Before long Lory had twenty pigs living in the house with her, then forty pigs, and then sixty pigs. People from miles around heard of her, how there was this lady—the Pig Lady, they called her—with enough love in her heart to accommodate every sick and injured or misfit pig ever. From Palatka to Bimini, from Espanola to Favoretta, they came, bringing Lory their extra pigs, and Lory, as the protector of the pigs, the shepherdess of a bona fide pig sanctuary, embraced them as she would long lost children returning from the wood. Come one pig, come all, get your pig butts in here and have some fun in the mud. “You guys are covered,” Lory told her pigs.

Word got out too amongst the wild pig boys back in the forest, all this about the hot young pigs running loose beyond the fences. They said to each other, “Man, I sure would like some of that!” and discussed the situation. They knew how sometimes when you rooted around weird places you ended up in a cage-trap, or got shot down from the window of a house or truck. Then you got strung up by your ankles and skinned and chopped into bits, no thank you. Playing it safe, they ran across the field at night, instead of during the daytime, and nudged the fences, gnawed on them and pulled until one wild pig got through. He found him a nice domesticated girl pig who was perfectly happy to make his acquaintance. He hopped right up on her back and started humping, grunting, peeing and pooping and having the best fun of his life. He ran back to the other pigs and bragged all about his great time.

In the nights that followed the other pig boys—there were five altogether—made it through the fence, and they too started getting on with some strange and having great fun. When Lory’s helpers, these wayward men whose muscle and motility Lory traded for beds to sleep in and let’s just say a beer or two in the morning, discovered what was going on, they fixed the fences and stood guard, protecting Lory’s harem diligently until the wild pigs finally decided to move on in search of new great wonders. The new babies left behind by the wild pigs would need at least twelve pairs of hands to count them on. Lory’s pig number went from 300 pigs to 520 pigs to 700 pigs and the number kept growing. Lory could not hold steady at any given number. Of course, her feed bill grew too, went from $1,600 per month to $2,600 per month. Her disability benefits didn’t cover this, not even close, so she bought her feed on credit. Her debt doubled. One day she was a mere twenty grand to the red, the next she owed forty. Her numbers grew in every sphere.

Her dad said, “Girl, you really ought to get rid of at least half of these pigs.” Lory said she would die should something like that go down. Her family believed her. John, her dad, wanted her happy, same as it would be for any caring parent, but quite honestly, a thing like this could not be good for anybody. A camera crew, Phyllis Redman and Eric Breitenbach, professors at a local college, had taken interest in his daughter. They went around asking questions of the family and making movies. Breitenbach did the filming, Redman took sound and asked the questions. She asked John one day what he thought of his daughter’s pigs. It wasn’t something he really needed to think on. He just said, “Oh, I like pigs, I think they’re all right, I really enjoy pork barbeque sandwiches, pork barbeque dinner. Pork chops, bacon, sausage. Yeah, I like pigs, I think they’re great.”

Lory’s pigs and debt were not the only thing increasing. So did the admiration she took in from Charlene, her mother who had been there for her from the start, as trying as this whole thing was at times. Charlene respected Lory’s mission when it came to the pigs. In Lory, Charlene saw a woman with a stronger sense of purpose than your average able-bodied whoever. When interviewed by the camera crew, Charlene said, “Maybe this is what God had in mind for her. Maybe this is the reason for her being in a wheelchair.” Lory never complained, never asked for help. She left only the things she could not possibly do for others to do. The thicker the mud, the tighter Charlene held on. The stronger the smells, the thicker the swarms of flies, the larger her love.

Had anybody anyway seen a more healthy, more vibrant, more attractive woman in a wheelchair surrounded by slobbering pigs? The healthcare workers didn’t think so. They’d simply never seen anything like it before in their whole lifelong careers. The wheels of Lory’s chair always were caked with mud. Her slender legs, shins wound with pink or blue gauze to prevent swelling, had a smooth lithic sheen, and what a nice set of toes! The shin-wraps gave Lory color, a unique style that additionally protected her against mosquito bites. As her cute little toes were often coated with dried mud, they were not as vulnerable when it came to skeeters.

As a child, growing up out in the countryside, Lory had loved all critters. She helped them whenever she could—the birds, cats, raccoons, mice. “Anything with a heartbeat in it,” one friend said of her. Lory also loved horses, but horses were too tall for a woman in a wheelchair. Pigs, on the other hand, were juuuust the righhhht size. Hello there piggy. Anything I can do for you today?

As Lory’s pig count grew, and her troubles grew, the insurance company started holding out on her, and her old employer, the folks she worked for when she had the accident, stopped following through on their promises. She felt abandoned. She felt like she was losing her pigs, failing them, so got ahold of some spray cans and painted SORRY PIGS I HATE MYSELF over her walls. A nervous breakdown here. She just did not want to lose her pigs that she loved. There was a court case going on. All of this was so stressful, so Lory just petted her pigs, tenderly scratched their underbellies, hocks, jowls. Oh the ears, the teats, the tongues, the wrists. If a pig died on Lory’s watch, Lory wept. If a pig went sick, and Lory knew he would die, she spoke to him consolingly, saying, “It’s a great place where you are going. Once you get there you’ll see what I mean. There will be grass everywhere for you to chew on, and you will see your momma.”

* * *

The camera crew rolled on. Bright were the days of mud, of cigarettes and white waddling geese, pig babies and pee bags. The yellow days with Lory and the Yazurlos piled up on top of each other until a whole year of bright days had passed by. There were dark days too, rainy days, days that were cold, and green days, every day a day filled with pigs, with pictures, with film, Breitenbach and Redman going around with a notion to save this element of the great Florida biosphere off County Road 90 East in west Bunnell—save, as in make safe against time and encroaching tragedy and decay and oblivion, at least in the way of a document, a proof that this locus of teeming life once was, this countryside magnet for wayward souls and wounded and unwanted or misfit pigs.

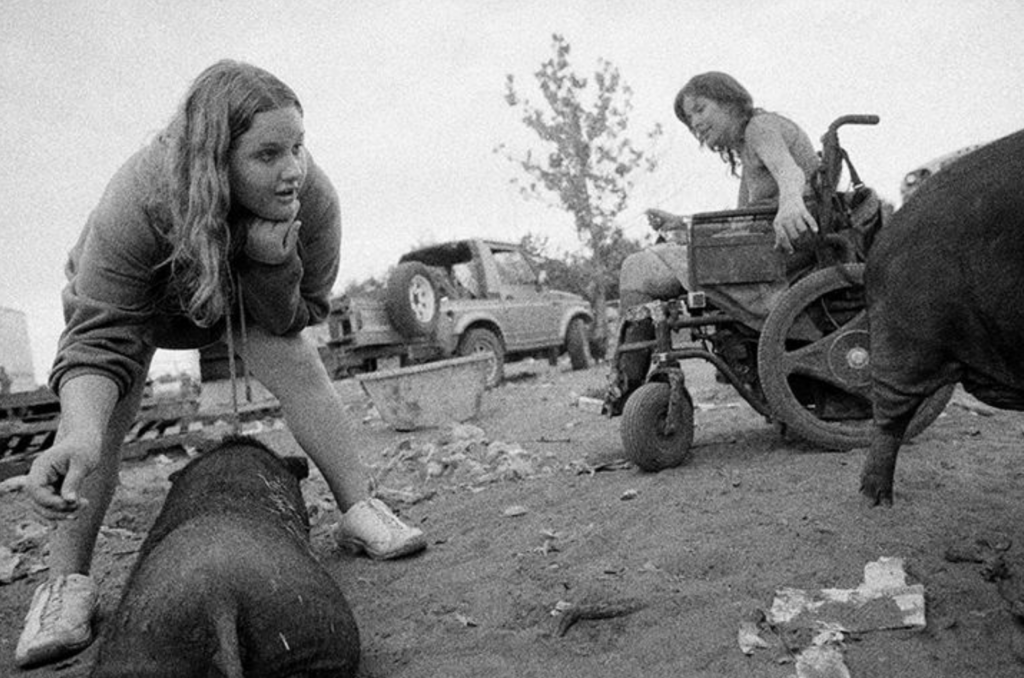

In Breitenbach’s collection of stills, we see Lory with her feed, Lory driving her chair through mud, Lory refulgent in sunshine, Lory ringing her pig bell, Lory reaching into her purse, and Lory with her buckets, sunken into her chair in a slinky kind of svelte luminosity and glamour to put your latest leading lady to shame.

In all of the photos, Lory is surrounded by pigs, and in this one appears to be talking to her pigs. She is dirty and, having grown up in the seventies I associate her look with Farah Fawcett and Kristy McNichol, the powerful goddess and ingénue wound up together in a wonderful mix of bombshell and empathy. As I have seen the Breitenbach and Redman movie—When Pigs Fly—I know, too, that Lory’s voice has a tenor I would not tire of hearing. I’ve got her address. Wouldn’t it be nice, I think, to go on a date with Lory.

Another photo shows Lory with her bucket and cigarette wearing a peculiar stretched-out leg warmer sort of thing on her head—her face is cupped cozily inside the egg of it, her expression fresh, self-assured and somewhat self-romancing. To me in brings to mind Obi Wan Kenobi. How absolutely adorable and cute! She is peering through her fence at her sustenance and purpose, a whole yard filled with oinking kicking snot-blowing pigs, as though she is getting away with something sneaky. There are so many pigs! Just look at them out there! Pigs and pigs and more pigs!

Question: What are the similarities and differences between quadriplegics and pigs? Both do not have complete control over their faculties. And Lory smokes, pigs munch. Lory cannot bear children—or can she?—while pigs work hard in the pleasures of making sucklings. Empowered and made happy by ringing her bell, so is it with pigs when their suckings suckle. Lory and the pigs are naturals, primitive in the heart of a land made holy in its promise to let pigs live. At Pig Tales, the name Lory gave her twenty-acre compound, pigs sleep comfortably, far from the crimes committed upon their species. Here pigs eat, and dream without fear of the butcher, his shiny array of skinners, boners and cleavers.

Breitenbach’s final image is of a pig on its belly in the dirt, resting below the outspread legs of a young girl, the girl bent forward, her face turned in observation of a second pig exiting stage left. If you travel through the girl’s legs, traveling the direction the pig would be traveling were it walking, you will encounter some wood pallets and a livestock feeder beyond which a pickup truck—every farm needs one—waits for use. Beyond the truck, continuing on further, is a tree, but then you must about-face. On your return voyage you will encounter the Pig Lady, hand reaching for, or perhaps withdrawing from, the pig moving out of the frame. A cycle here. We go in, move forward, turn back at an angle. The things that come to us that we love leave us. When looking at the picture, I hear a cry: “Wait!”

I myself grew up in Florida, and on occasion return. As I had an upcoming trip there, I thought, Maybe I can visit Lory. What’s up with Lory these days? so looked her up on the internet, half-imagining that I could realize my fantasy to go on a date with her, maybe drive her to Panera Bread where we could drink coffee and talk stuff over, have a light lunch then take a wonderful drive through the countryside. After typing “Pig Lady” into the Google search bar, I found out that Lory’s pigs were gassed while in transit to a dumping ground. In the comment sections of the articles about Lory and her pigs, folks told a different story, testifying that Lory watched her pigs get killed, get slaughtered, get carried off under the pretense that they were diseased and presented a health hazard to the larger community of human beings. After the slaughter the court ordered Lory not to mess with pigs for a year. If she messed with pigs she would be punished. Lory had had her pigs. Now Lory was pigless. She’d gone from hero to zero in the space of a dime.

Then I read this: “Yazurlo was in the van, unable to get out.” Continuing the story, FlagerLive.com said, “After the fire, the van was towed by John’s Towing of Bunnell. John Rogers, owner of John’s Towing, said: ‘We have no record of changing a tire last night.’” The writer for FlaglerLive.com, said, “Lory would eventually be found out of her wheelchair and between the two front seats.” The writer mentioned the words “foul play,” and reported that the State Fire Marshal was running an inquiry, and had not as of yet “ruled out the possibility that a crime occurred.” The writer for PalmCoastObserver.com wrote: “Two calls came in to the Sheriff’s Office’s dispatch center starting at about 2:03 a.m. Sept. 22.” The writer for the Daytona Beach News Journal wrote: “the blaze was so intense that officers could not get close to the vehicle.”

So much for my date with the Pig Lady of Bunnell, whose world erupted in a pain suffered by witches and necromancers throughout history, the bright red rod, fire somehow just punishment for women accused of shapeshifting or having familiars.

* * *

Do you recall, as do I, the Bible tale where Jesus stumbles upon two guys who have jumped from a graveyard acting crazy and being ludicrous in their speech? The story appears three times in the New Testament, and what we gather when piecing the tellings together is that the men were dirty and naked. The men had a history of getting chained up and then breaking through their chains, so probably had scabs on their bodies and bleeding sores and were super smelly. People said these guys were possessed by demons. When the men saw Jesus coming along the road their way, they were terrified, and said, “Jesus, please, if you’re going to banish us, send us into those pigs over there!” Jesus looked over at the pigs grazing peacefully on the hill. There were about 2000 of them. Jesus looked back at the men and said, “Sure, go ahead.” And so it was. The 6000 demons left the two men and entered the pigs, about three demons for each pig. The pigs then rushed down the hill and over the cliff where they fell into the sea and drowned, ostensibly destroying the demons that had been inside them, or sending them back to perdition. That’s when people came out from the village with sticks in hand, shouting “Jesus, get you out of here! You have killed what we love!” They cast Jesus from their midst, but Jesus had only granted the demons their wish. Was Jesus saying pigs’ lives don’t matter? Was Jesus saying it is better to kill 6000 pigs than watch two men walk around naked and dirty and distracted and angry, maybe frothing at their mouths? The writers described the demon-possessed men as violent, yet did not mention any crimes.

After allowing the demons to enter the pigs, Jesus moved onward to his crucifixion, and in the centuries to follow folks drooled over His body, ate It as though at a trough, drinking His blood and going on about how truly awesome and undefeatable, how delicious, He was, and is. The more generous reading of the story, despite what the saints may have said, would be that Jesus puts pigs on equal footing with humans, for it was the pigs, not Jesus, who got rid of the demons whose purpose is to torment and spread havoc and paranoia. The pigs practiced self-sacrifice. The pigs had gone face-to-face with evil, serving God in a manner not so different from His imminent climb to Golgotha.

*

Photographs of Lory Yazurlo courtesy of Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach

© Eric Breitenbach