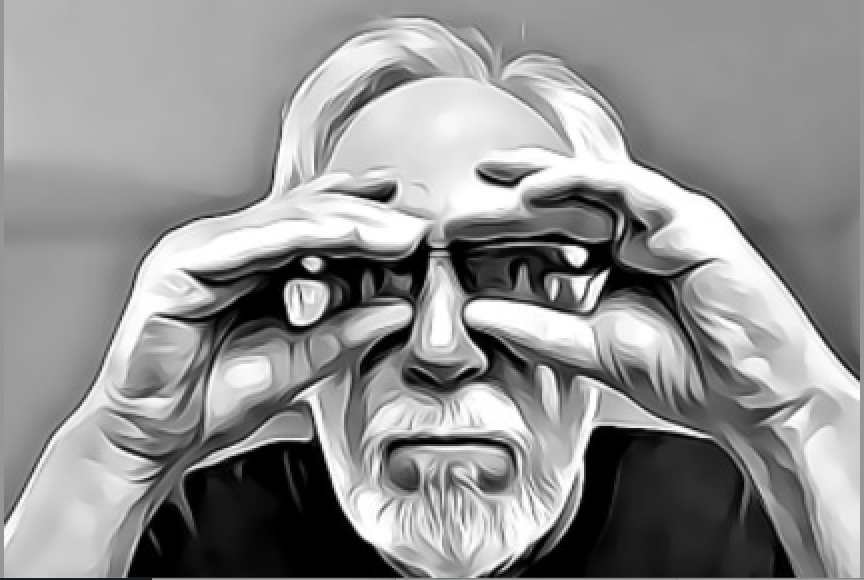

I didn’t see this coming. As I get older, I’m getting sadder.

It’s not depression. There’s a difference between sadness and depression. Sadness is clear-eyed and frank, while depression is often nebulous, clinical, chemical. Sadness comes from having our expectations—the things we were taught to expect, to believe in—dashed, or unmet for too long. The wool has been pulled from our eyes so that we can now see things with a stark clarity that is both unexpected and undeniable.

It’s a function of age, the way the propaganda of youth gets peeled away like paint on a car left out in the weather for decades. The glossy shine goes first. Then tiny pits in the surface get picked at and abraded until the integrity of the coat is lost and the bare metal starts to show through. Eventually the protective qualities of the paint are revealed to have been temporary, possibly even an illusion. In the same way, the tools they give us when we’re young to be able to go out into the world with any kind of fortitude—optimism, self-confidence, trust, faith in others, vision, doggedness, compassion—are chipped away at as we live life, and by the time we’re in our sixties and seventies (I’m sixty-five as I write this) we’ve seen some things. It’s hard not to chuck all those tools as having been not much more than crutches, though crutches, I admit, are necessary tools.

Now I look at the world and understand that whatever optimistic ideas I had about progress were put into me so I wouldn’t give up along the way. You gotta have hope, they said. Don’t stop believin’. And I have believed, up until the recent era, believed that humanity moves generally in the right direction (in spite of obvious evidence that people have always and will always fight, take advantage of one another, kill, steal, hate, denigrate, marginalize, ostracize, deprive, mock, and torment, all the while preaching love). When you’re younger you look at these things and imagine that they’re the exception not the rule. Society would break down if they were widespread. You can’t see the ways society has broken down, the decline is so slow. But when you’re older you see the long course of things. You have the wide-angle lens young people can’t access.

When I was young, back in the ‘80s, I was able to compartmentalize tragic things in the larger world. AIDS crept into my consciousness, and I acknowledged it, considered it, empathized with victims, but I also played on a softball team and ate out and was happy when the St. Louis Cardinals won the World Series in ’82. I absorbed the Russian war in Afghanistan and world famines. I took in stride the loss of life in the Challenger disaster, and I was aware of the chemical leak in Bhopal, India, that killed 15,000 people all told. These things didn’t affect my ability to enjoy rock concerts and weekend parties or to pursue my writing goals.

In the ‘90s, as I zeroed in on forty, came Ruby Ridge, Waco, Oklahoma City, the first World Trade Center attack, the first Iraq war, a friend’s death of AIDS, estrangement from my father, new right-wing political cynicism, OJ, and I met my wife and married her in Italy, bought a house, wrote novels, and lived happily above all those things. Today, I’m embarrassed by my disinterest.

I can’t even say I was sad about these things, though I was saddened. Their effect on me was always short-lived and easily replaced by my daily priorities. Now, so many things sadden me that there’s hardly ever a moment when I’m not aware of at least one of them, often many at once. There is nothing I can do about them, so the sense of helplessness contributes to the overall feeling that the world, on large and small scales, is a failing place.

But I coexist in this flawed world with young people who are now where I was in the ‘80s. They’re starting careers, falling in love, having babies, trying to score Taylor Swift tickets, looking ahead with hope even if it’s naïve hope. Where I was ignoring the threat of nuclear war, they’re carrying on in the face of catastrophic climate change amid the rise of worldwide fascism and they’re doing just fine. It’s the nature of youth to pace yourself. Things change as you go.

I know existence has always felt like this, especially to older people. We’re told to look at the shiny objects of new inventions and pleasures and not at the way inequality only seems to get worse, and humans never change. Older people through history have shed their optimistic shells, observing that suffering is still here, dehumanization, contempt for the Other. No lessons have stuck. We’ll have to start over and erase our own era of experience if there’s a chance to make things better for those who come along after us.

And we can’t help feeling that it’s already too late.

Sadness is natural at this time of life. Our own end comes into view, like the way the road on the far horizon seems to penetrate the mountain. Where they meet, we stop. It is only human to feel sadness that the journey will definitely end, sooner than later. The days are suddenly countable.

But I’m embracing it, this sadness coming along at the back end of my middle age. Finality is here, and awareness that we haven’t made much of a difference in the world. We were small and insufficiently attentive to how fast it all goes. We thought we had time to patch things up and take baby steps forward. It wasn’t supposed to be like this. That’s the bottom line after all this time, and it must be accepted.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this, and now whatever redemption is out there is for the young to seize.