Where am I from? When asked that question, I usually reply, Greenville, South Carolina. Then, tag on that I am also from our family’s Air Force trek. We circled the world and came back again to South Carolina. I am molded by this migration. The older I get, supposedly the wiser, but I am only wise enough to realize that I do not know my parents’ full story. So, I write to understand and connect the pieces. This photograph is my parent’s senior class picture from Fountain Inn Negro High School. It helps me to connect—with it I stitch and piece my familial history. From this picture, I begin to understand my roots a little more. As a child, when I looked at this photograph, it took me in, but I did not understand the miles my parents had to travel literally and metaphorically to get to school.

I am often asked why I write about the past. Often asked, why not leave the past in the past? Yet, the past has so much to teach me–to teach us. When I look at this picture and I talk to my mother about it, I realize how much I do not know about my parents and what they went through to get me here. It is through their striving; I am able to reside in the world as both a poet and a teaching artist. The more I delve, the more I understand not only what my parents endured, but what other African Americans encountered.

For the last decade, I have been carrying this photograph in my heart. I have been holding it in my psyche. I began talking to my mama more intentionally about it and asking her about all the people pictured. This group photograph fills me with both wonder and pride, especially when I look at my parents: Johnny Redmond and Jeanette Todd. To see them in their youth speaks to me of promise and also fills me with questions about the precarious nature of our origin story.

My mama stands on the first row second from the left. She is a dark-skinned keen face beauty with a tiny belted waist. She radiates with class and with a coolness of the times. She sports an A-line skirt with two-tone pockets an outfit complete with slouching bobby socks and saddle oxfords. My father stands slightly to the right behind her on the second row. He is strikingly handsome with a stoic chiseled bone structure. He gazes directly into the camera with a hint of a smile demonstrating a determined self-possession. He is dapper and the only one of his classmates wearing a bowtie. He is a standout even then. Their whole class is dressed up for the occasion. To me they look older than their years. Yet, their clothes and posture present only a small but important part of their stories. I see this collective in their Sunday best and know it belies many of their sharecropping impoverished circumstances.

The name of my parents’ high school Fountain Inn Negro High School says it all. It sets the context of our African American plight. The division is in the name. Though my parents and their classmates made the best of their circumstances, it does not diminish the systemic legal hate they had to battle. Negro. There it is—a classification—a division they themselves did not create, but one they were born into. One they had to live within its confines in the South. I am often perplexed and upset when I hear when people question black solidarity and unity. Why are there black churches? Why are there black colleges and universities? Why is there a Black History Month? Why do all the black children sit together in the cafeteria? It is as if they have no understanding how this country was built and how the institution of slavery is linked to segregation? I wonder often why is there so much systemic racial amnesia in America.

My parents attended an all-black school not by choice, but by law. They endured a separate but not equal education. In 1895 South Carolina implemented racial segregation in public schools. The next year, the Supreme Court of the United States mandated separate black and white Americans in public places. My parents had to navigate schooling and their everyday existence under the harsh circumstances of Jim crow.

They/we sang the Black National Anthem, Lift Every Voice in Sing. It was and is a cultural practice never ever meant to exclude or to sew division. It was meant to combat it and shelter us in an America that did make room for us. The poet James Weldon Johnson wrote the poem and his brother set it to music to give us a sense of pride because our place in the Star-Spangled Banner included us like this:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

The fact that my parents were even able to be in school was tenuous. My mama went to school with her first cousin, J.W. Rogers. Mama says they were more like siblings. In the picture he is on the third row in the center next to my father’s first cousin Mac Redmond. J.W. and my mom were both sent to live with their Uncle Willie and Aunt Carrie, so they could attend Fountain Inn Negro High School, as Waterloo did not have any options for black students at the time. Though mama did not want to leave home, her mother insisted. These were my mama’s steps out of the impoverished circumstances in which she was born.

Going to school, however, did not provide an escape from sharecropping. Mama recounts that the white landowner cornered her Uncle Willie one day and told him to make sure that J.W. and Jeanette worked the land to make sure the farm was kept up. Uncle Willie spoke up, “my children will work the land on the weekends, but they will not miss a day of school.” His stance was firm and extraordinary for many black parents of the day. He stuck to his word. Mom recalls that not all their classmates were as fortunate. “Melvin and Minnie, the two brothers on the back row to the right, came from a family of thirteen siblings. They had to miss school often to farm.” Mama said, “Come harvest time, the classroom was skimpy because so many of our classmates had to help their families work the field.”

My father was a hard worker too—but he did not work in the fields. His father, my grandad, was a plumber and worked for the city. My dad played piano for Bethlehem Baptist Church. He often played the piano in the Peg Leg Bates Gymnasium at school between breaks at school or recess. The students would gather around and sing and dance while dad played. He was a musician at heart. Yet, he took jobs in the hospitality industry and restaurants. As a high school student, he worked as a hop-boy on roller-skates at a diner off 276 in Fountain Inn. Simultaneously, he was a bus driver for the school at the age of fifteen. Dad was able to buy a car while he was in the tenth grade. This allowed him to visit mama when he could.

Later he moved to live with his Uncle John Albert so he could work on the weekends in downtown Greenville at the Poinsett Hotel as a busboy. He worked at the hotel for approximately two years. Eventually, he tired of being called racial epithets like boy while clearing tables. These encounters with white patrons fueled his rage and he decided to leave the South via enlisting in the Air Force. My father never forgot this poor treatment. It marred him.

When I look at this picture. I keep staring. The more I stare the deeper I go. I begin to understand just a little of what my parents endured. I keep staring and writing to piece together my family’s plight. Mama leaves Laurens County at age fourteen to attend Fountain Inn Negro High School and eventually marries my father and goes on to travel the world for twenty-one years, but it does change where we came from. I often think about the fragility of our existence then and now. As an African American poet, I dig. The more I learn. The more I want to know.

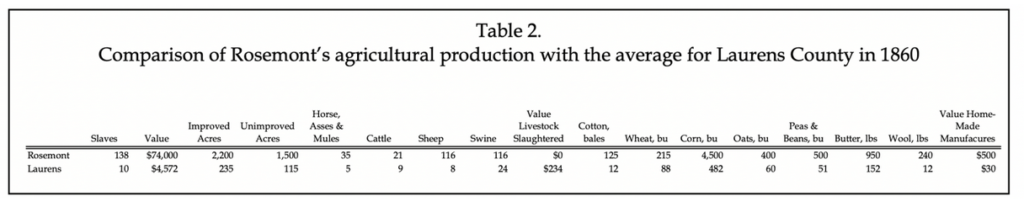

My great grandmother’s last name was Cunningham. She was from Waterloo, South Carolina. Her father, Allen born in the 1840s was a Cunningham also. I am not sure if I will ever know for sure, but I surmise that my family is linked to the Rosemont Plantation. The owners were the Cunningham’s of Waterloo, South Carolina. The area is only but, yay big. So, it is not a huge leap to think my family is connected to the plantation. I believe I found my ancestry at the plantation through a survey titled Revisiting Rosemont Plantation by the Chicora organization. I believe that my ancestors are here with no names, just a crude categorization of the enslaved. I believe my people are bound up in this chart.

How do you break generational poverty and illiteracy? It starts with my grandmother with a 3rd grade education. She insists on her daughter being educated. Ms. Estelle Latimore was mama’s elementary school teacher. She was from Greenwood, South Carolina about thirty miles from where they lived. She traveled to Waterloo and taught at the one-room schoolhouse. She boarded at their house during the week and traveled back home on the weekend. She taught school to adults in the evening because many of them could not read or write, my grandmother Katie Latimore included. This is how my grandmother with only a third-grade education furthered her education and strengthened her reading and writing skills. My grandmother wanted her daughter to have a better education. Her elder siblings Jannie Mae and Doug stopped school in the 7th grade. Mama was the first in her family to attend high school and graduate. Leaving Waterloo was a miracle act brought on by a mother’s love. Grandmother ensured mama made it to Fountain Inn Negro High School. This step was the tide turning.

Fountain Inn Negro High School linked her fate with my father’s. It was how we came to be. I believe in fate and as a young girl, I found their story incredibly romantic. I thought it was dreamy that my parent’s met and fell in love at Fountain Inn Negro High School. Recently my mom told me otherwise. “Your daddy’s uncle killed a man.” I leaned in and told my mama, “Do tell.” She said his aunt was being beaten by her husband. When she showed up bruised and battered, her brother warned her husband, if he laid hands on her again that he would kill him. Good as his word, when she showed up at church beaten, her brother went out to the field where he was working and shot him dead. He was sentenced to a chain gang in Laurens, South Carolina. Once the family loaded up the car to visit him. The car was packed with family and homemade food for his uncle. On the way to the prison their car broke down in front of a ram-shackled house. A four-year-old girl was at the door and ran to tell her grandfather about the family with car trouble. Her grandpa came out and fixed the car. In the car was a four-year old little boy.

When my mom was sent to Fountain Inn Negro High School on the first day she walked into the school. She says that my dad remembered her from that time she was standing in the doorway when their car broke down. Mama says wistfully while telling that story, “Your dad always had a photogenic memory.” When I heard this story, I looked at my mom in disbelief. She states in a matter-of-fact voice, “I thought you knew.” My parents meeting was less of romance, but more of a past familial love gone wrong woven together by vengeance, gun shots, family honor and blood.

Our migration story began with my father’s flight out of the South in 1954. This photograph is a vital keepsake that helps understand where I/we came from. From it I gleaned the past. From it I continue to piece our history together. I bristle when people ask when I became an activist and started standing up for social justice. I was born in 1963. My parents were born in 1936. We have been trying to survive and thrive in this country that has made very little space for us. We want what all Americans want: a better life for ourselves and our children.

Mama tells me she was aware of the substandard funds their school received. She compares the school buildings and the lack of books in the library and inadequate supplies for learning to the white schools in the area. She says, “If it were not for Clayton “Peg Leg” Bates they would not have a gymnasium where they had P.E., sporting events and gatherings. The photo takes place on the steps of the Peg Leg Bates gymnasium. The young woman to mom’s right is Mariam Fields, Peg Leg Bates’ niece. His nephew Robert Bates is the light-skinned young man on the last row standing behind mom’s cousin J.W. Rogers. They had pride in their school mama recalls, but they were all aware of its shortcomings due to inadequate funding from the county. She told me that area white schools had ten buses to their three.

She said they protested and their principal, Gerard A. Anderson led the charge. He suggested that they go to the superintendent to fight for equal funding and support. I can hear a note of admiration when mama speaks of her teachers. She remembers Mr. Pendarvis who taught Biology. Mr. Wright who was their coach. She said that most of their teachers came from the low country. She speaks most highly of Ms. McDuffie, her home economics teacher. Mama loved this class and was one of Ms. McDuffie’s star students. She taught her to further her clothes-making skills. She also strengthened mama’s cooking and homemaking skills too.

My mama speaks of classmates more like a family. They were the Fountain Inn Bulldogs, and their school colors were burgundy and gold. They contained a sense of school pride. They had a basketball team on which my dad played, though he was short, they could count on him to make long shots. They had a glee club and a choir. Mama admits that she had no business joining glee club because she could not carry a note, but dad was in glee club, so there she was. They traveled from school-to-school singing. It was a time full of joy.

Mama tells me about their senior class trip and because they were all so poor. They only went to Paris Mountain for a day trip only 30-40 minutes away. I surmise that they more than likely went to Pleasant Ridge State Park which was designated for non-whites. Paris Mountain was for Whites only at the time. The division has been sewn deeply in the fabric of America. I can feel as she recalls the moments of talking about this picture, how her heart is divided by what she/they had to combat: poverty and racism.

When my mama travels back, I lean forward to gather the whole story. From her I weave the threads of our complicated history of how I/we came to be. We are from this layered past. The division in the name of their school and throughout this fractured America which still exists. In this photograph there are so many stories not just mine or ours but of the collective. There are so many stories not written in books. So, I dutifully and passionately write my family’s origin story. I do my best to piece it to a greater whole. The whole quilt of where we come from, a worthy history stemming from my parents who graduated in the last class of Fountain Inn Negro High School.