It’s one of my favorite pictures even if it is a little blurred. My family—mother, father, older sister, and I—stand in front of our concrete bungalow in Ogbomoso, Nigeria, my birth place. I’m probably four. We’re wearing nice clothes so it may be a Sunday, though my sister and I wore dresses and white socks with shoes every day but Saturday so it may simply be an ordinary morning before I’ve run about the compound and gained a band of dirt around my neck. On second thought, my father doesn’t look quite formal enough for Sunday.

I’m nostalgic about this photograph and all of the pictures I have of my childhood in Nigeria. We didn’t live in Westernized cities but rather in traditional towns. Ogbomoso had a population of 30,000 when I was born. The one story brown homes seemed to sprawl out forever. American Baptist missionaries’ homes were built on large compounds, along with a seminary or a hospital or high school, and children had free run of these large mission outposts. When I was sixteen, I came to live permanently in the U.S. and I have never truly felt at home here. So I return to these photographs often and this fall I shared this particular picture on social media as we all do, to convey something about our experience. It’s always been my feeling that I’m a foreigner on U.S. soil, though I’ve been a citizen from birth. It’s not a citizenship I would have claimed in my youth. The U.S. was strange to me.

In the photograph, caladiums fill the planters around the deeply shaded porch. I can see the screen door and know exactly how it felt to open it and the breeze that came through it. I can feel the concrete floor of the porch and the sisal rug in the living room under bare my feet. I see the route through the living room, dark after coming in from the bright light of mid-day, through the dining room and into the kitchen where I reach into the refrigerator for a cool drink of water. I see the smooth finish on the piano as I pass back through the living room, the turntable where I listen to “Peter and the Wolf,” the woven leather stools, or tim-tims, that serve as foot-rests for my parents. And I’m back outside and in the present looking at the photograph. There is the small tree at the end of the walk that had leaves in the shape of a Valentine, and I know that on the other side of the house are the guava tress I climbed every day. I know a 1957 Chevrolet station wagon is parked in the sandy driveway though it doesn’t appear in the photograph. And I recall exactly where the swing set is placed under two hardwoods in the front of the yard by the road. I know that on the other side of the fence in the back is a Nigerian home and that the chickens belonging to that family regularly come through the fence into our yard. I can conjure a groundnut lady who comes often to sell her wares, the hospital up the compound road that is full of Nigerian patients, the nurses in the wards who are all Nigerians, and Mr. Bolarinwa at the carpenters’ shed, a handsome Nigerian man, who builds fine furniture.

Photograph Courtesy of Elaine Neil Orr

All of this floods back to me as I post the photograph to Facebook, as if the image might convey my deep devotion to my parents, who are gone now, and my affection for my sister and our shared upbringing, my love for Nigeria, especially Yorubaland, as if the photograph might trail all of this glory and devotion onto social media. One hundred and fifty-six people like or love the photograph. My friends are solicitous. What a beautiful picture. I loved your parents. What a special upbringing. Would so love seeing more pictures of that time. Until an acquaintance is not solicitous. Is that Nigeria? It looks like American suburbia. I’m not sure of her intent but I patiently explain how our homes reflected modest American designs of the period. This concrete cottage is similar to the fifties era bungalows in almost any Southern town: front porch, central living and dining area, rooms to either side, with a kitchen and eating area at the back. A breeze could move from front to back all day long. Feeling an edge of wariness in my acquaintance and in me, I mention that Nigerian universities included faculty housing built on similar American designs.

The acquaintance—I’ll call her Lori—isn’t interested in my comments on architecture. She doesn’t see the fuller picture I do, doesn’t hear the Yoruba drums that sounded day and night and filled my dreams, or the Yoruba worship services we attended, or see the women in the pews with their extravagant gold headdresses. She is firmly set on how spacious and American the house appears. I want to explain that that’s not the point. This was my home. I was loved here. I first loved the earth and its people here. I thought the globe was made primarily of Black people with a few white ones sprinkled in.

In her next comment, Lori, who is a white American, writes: Full disclosure. I am against missionary work as I find it racist and an attempt to colonize people from their own cultures and beliefs. I have spoken out against my own conservative religious racist family for supporting white missionaries.

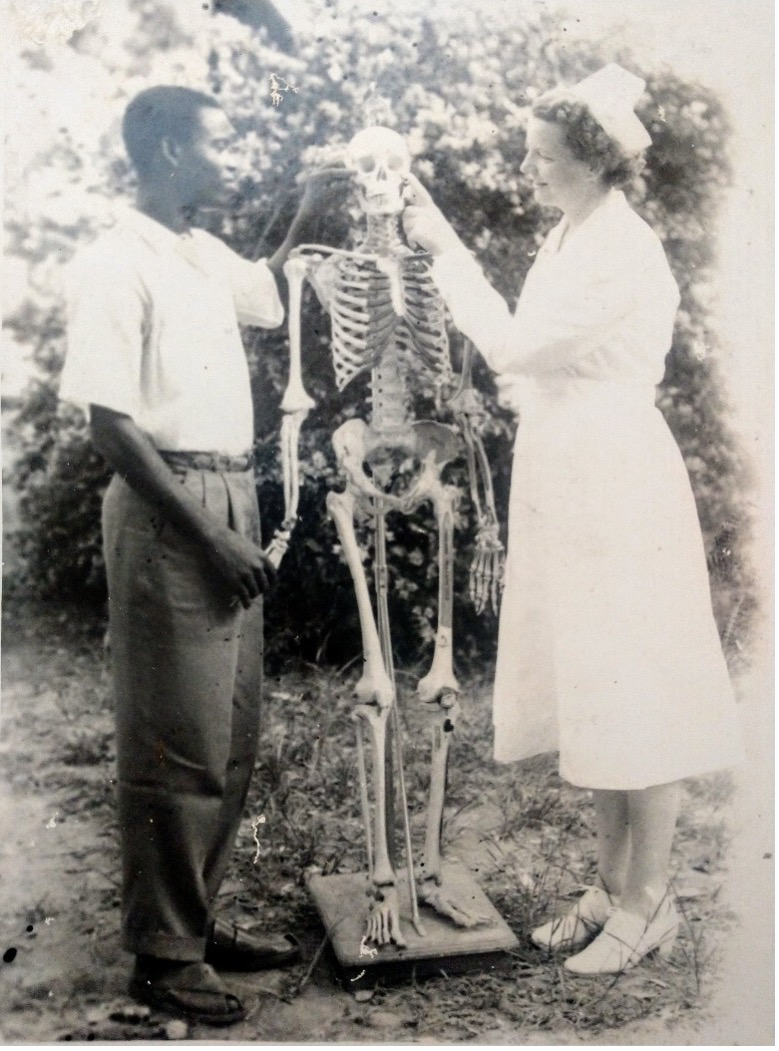

Why is this person saying these awful things about my parents? The word “missionary” clearly triggers her. My parents were paid by the Southern Baptist Convention, but growing up, I saw them going off every morning to keep the hospital running and to teach in the nursing school. What most struck me about my parents was how capable they were: my dad could do arithmetic in his head and my mother knew all the parts of the skeleton.

Photograph Courtesy of Elaine Neil Orr

I feel fiercely defensive. My parents weren’t racists. But I stay calm. I tell Lori that I understand postcolonial theory. I teach it, for heaven’s sake. I know missionaries followed in the footsteps of colonialists. But I assert quite firmly that I have encountered much more racism in the U.S. than I ever did in Nigeria, and I think this will shut her up, because it’s true.

Instead, another friend (I’ll call her Joan) jumps on the band wagon: I have to agree with Lori on this about the overall concept of missionaries. The agenda was to convert and coerce, colonize etc.

And what is your authority? I want to write.

By now, I’m talking loudly with my husband, who knew my deceased parents well, who travelled to Nigeria with me when we first married and saw the compound I was born to and the way missionaries worked in hospitals all day or taught in schools. He knew my parents’ liberal political leanings, my mother’s feminism, my father’s humility. I’m incensed at Lori for turning them into caricatures.

When I was a girl and attended an American boarding school, African-American students attended—a decade before schools in South Carolina (my parents’ home state) were integrated. My first crush was on an African-American boy. Because Nigerians ran the country and the banks and universities and churches and everything else except the mission compounds, it seemed obvious that Nigerians held power. No one was “Black” because skin color doesn’t need to be pointed out when everyone is the same (except for the white folks or oyinbos, of which I was one). But people with darker skin than mine ran the show.

Regardless of how I respond, Lori and Joan are not persuaded. The debate escalates. I defend my parents, pointing out how they volunteered in post-war Biafra after the Nigerian civil war. They ministered physically to any Nigerian who needed help. Many were Muslim or held their traditional faith. I make this point because Lori’s friend has claimed that any gift offered by a missionary is given as a bribe for conversion.

Eventually Joan drops me as a Facebook friend but Lori does not. I don’t change her mind about my parents and my upbringing, and she doesn’t change mine.

For a day or two, I experience the peculiar damage one feels about an argument one senses is not really over. And then the episode fades. I leave my photograph up. Christmas comes, a new semester of teaching by Zoom arrives. Life goes on. But I can’t quite shake the discomfort created by the Facebook back and forth. My parents weren’t racists. I’m certain of this. They treated every Nigerian they ever met with utmost respect and I was taught to do the same. They were horrified by U.S. American racism. But somehow the dream of my childhood is punctured.

It’s not until spring, as I am taking a walk, that something shifts in my brain, like a lock might jiggle open, if, say, the lock is on the back of a lorry traveling rough terrain. I can’t say exactly what creates the vibration that creates the shift: a bluebird winging by? A first iris? A stone under my shoe that causes me to skid?

Something comes to me that I have not wanted to know.

But wait.

Something else happened before the walk. I see a photograph circulated on social media by one of my childhood friends, a white American like me whose parents were missionaries in Nigeria. In her picture, several very young white children are engaged in a sports day event. They seem to be doing the duck walk, which I remember doing as a girl. If you’ve ever done it, you know how awkward and absurd-looking it is. You squat and hold your ankles and try to move one foot forward at a time. The result is a kind of waddle if you manage to stay upright. I dare say few adults could manage it. The duck walk requires enormous flexibility and powerful leg muscles. Children can do it because they are still dexterous and light weight.

In the photograph, the children are being watched by their parents, which is why this black and white image exists. This photograph is shared on a Facebook page devoted to adult children of missionaries. All of the remarks are nostalgic. The missionaries and their children, my peers, are identified one by one.

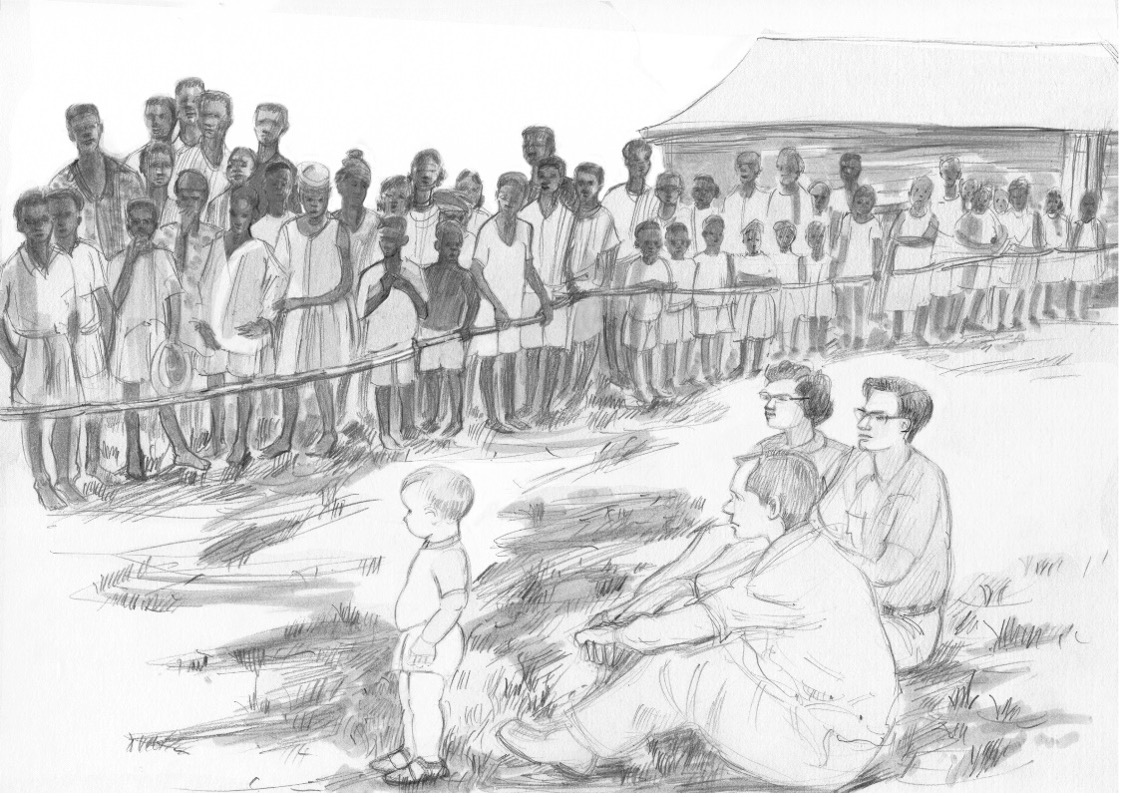

But here’s what sends alarm bells off in my mind. A few feet from the small grassy field where the duck walk is taking place to the amusement of loving parents there is bamboo fencing and beyond the fencing are dozens of Nigerian children and young adults squeezed in, looking on.

But that fence. It screams keep out.

Sketch inspired by a photograph, by Laura Murphy Frankstone, commissioned by the author

The Nigerian children were not invited inside the fence to participate. Why? Why was it so important to stage an activity for white children only? In order to give them an opportunity to experience life as white children? The image reminds me of pictures of American swimming pools for white children with Black children looking through a chain link fence.

I can recall instances in my childhood when Nigerian children gathered to watch us, usually when we were away from our large compound, say, out with Aunt Haiti Gardener, who spent much of her time without another white person, deep in the forest, and ate in an open room without windows. When we visited her, children crowded around to look at us eat. We must have seemed peculiar with our plates and forks and spoons and multiple dishes. But for the most part, the fencing was far enough away from my daily play or the compound was isolated from the town and so Nigerian children didn’t spend the day hugging the fence, watching me.

Still, what begins to dawn on me during that walk is that my extreme discomfort with Lori’s comments is not her attack on my parents but on my childhood. I lived in a bubble of affluence as a girl in Nigeria because my parents were white Americans. In the past, I have deflected this knowledge in all sorts of ways, for example:

Wealthy Nigerian children also lived in bubbles and had nicer cars and bigger houses than we did.

We spent significant time in community with Nigerians: at church, in Sunday School, shopping in the market, at Kingsway department store, at the hospital, in chapel, swimming at the river.

My mother was an intellectual and read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart when it was published. She educated herself to the political realities of missionary work and the colonization of Nigeria, and she sought to learn from Nigerians and to practice nursing with respect for traditional ways of doing things. For example, she thought it an excellent practice for women to carry babies on their backs and urged against imported formula for infants. She was a writer, but her writing was devoted to helping Nigerian women who had formed their own “Women’s Missionary Union” and were doing their own missionary work.

My parents were the missionaries and they did medical work, not evangelism, and I was just along for the ride.

All of those deflections are true and not the point. I still lived a childhood of privilege because I was a white American in Nigeria. Even if my parents were medical missionaries and even if their efforts led to better health conditions in the regions they served, mission work is based in a conviction of superior ways of knowing, be they spiritual, scientific, or mechanical. Tractors are better than hoes; the Bible is better than folktales, certainly better than “idols”; cleansing a wound with clean water is essential and anti-malarial drugs save lives. Some of these claims are facts and are undeniably true. But knit together as a whole cloth, the mission message creates a tent of belief in which the white man’s way is superior. All kinds of writers, beginning with Achebe, make this point better than I can here.

My epiphany is more personal. What I realize when the blue bird wings by or the pebble causes my foot to skid is that even if my parents were pure as the driven snow and never entertained a racist thought in Nigeria, I cannot extract myself from the systemic racism that created the bounty of my youth. I was a white child in a West African country whose playground was a compound so large—one hundred sixty acres—that I hardly saw the fencing that surrounded it. In most cases, the forest came right up to the edge. I seldom saw the folks on the other side. They were invisible to me even though I saw them immediately when we drove out of the compound in our Chevrolet. Surely folks passing along by a footpath on the other side must have wondered why we didn’t do anything with all that land, why we didn’t farm it. We just ENJOYED the land, enormous amounts of land for white children to cavort on.

Why? Why weren’t the Nigerian children invited to do the duck walk? If they had been invited to race, they would have won. Is that why?

Why didn’t we live in town? There were all kinds of dwellings we could have occupied in Nigeria at that time, lots of new concrete homes and apartments built much like the mission houses. Why were we fenced in? To reproduce an American life for us? To keep us safe? From what exactly? In the western part of the country where my family lived and most of the mission was located, we were safe even during the civil war and would have been evacuated if we weren’t. We could leave.

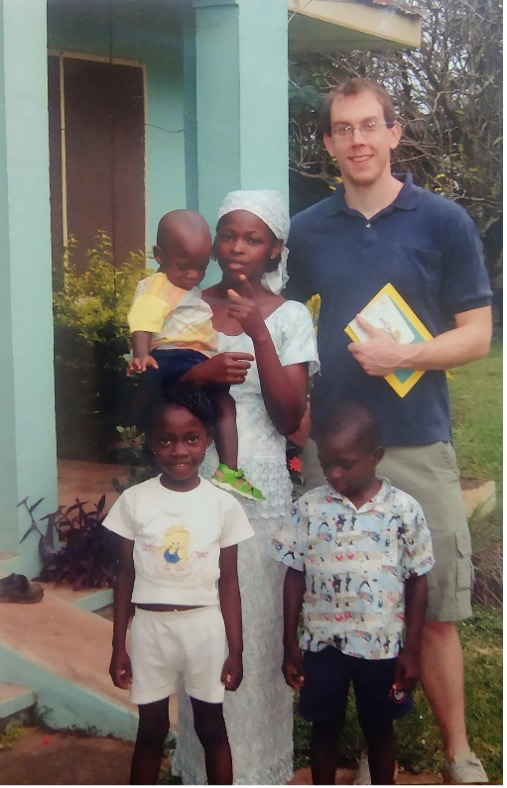

When I traveled back to my birthplace in Ogbomoso with my son in 2007, all of the compound homes were occupied by Nigerian doctors and nurses and administrators. One afternoon we visited the doctor’s family living in “our” old house. They kindly let me walk through the rooms with my son and point to the spaces that are written in my body like my DNA. The experience is a nice coda, but it doesn’t change the truth about my girlhood and white privilege.

Photograph Courtesy of Elaine Neil Orr

I have made it a foundational myth of my life that I grew up less racially segregated than my cousins were in South Carolina, that I experienced an upbringing in which Nigerians were treated as co-workers in the mission, that I am less racist than I would have been if I had grown up in the U.S. But while we didn’t have “colored” entrances, it may be that often we simply didn’t have entrances. While African-American children could come to the Baptist boarding school, Nigerian children could not. And I didn’t go to theirs.

My epiphany is personal but it is also national and even international. This awakening comes to me at a time when many white Americans and white people globally are coming to terms with our privilege. The pebble that caused my foot to scoot, that caused my mind to shift, was an accidental slip setting up a moment of enlightenment that began with Lori but was also set in motion by our era of racial reckonings.

Poems of innocence and experience.

It’s time to pull the plug on innocence.