Ollie came running up the front sidewalk, sleet pelting his bent head and hunched shoulders, and when the porch light fell over his wet figure, I realized that idiot was cradling a baby in his spindly arms. He’d called an hour earlier, sobbing from too many two-for-ones, and while he boo-hooed about some recent fuck-up, I warned him to stay away from us. Mick swore he’d kill my brother the next time he saw him, and now here he was, shivering on the other side of our front door, carrying a child still too young to hold its own head up.

“Mick’s sleeping,” I whispered, letting my brother into the house. “That your baby?”

I snatched the child from my brother and rocked it in my arms, hoping to keep it quiet. The cold infant stared dumbly at me, and before it finally blinked, I thought it might be dead. Ollie dropped onto the couch, as if he’d just worked a double, but if he had plans of sleeping off this mess, I ruined them by kicking his ribs and telling him to hand me the blanket. The crocheted afghan felt maybe too rough for the young one’s softness, but it was all we had. Once I wrapped the blanket around it, I looked in the fridge and wondered if babies that small can drink two percent milk. If so, how would I feed it? Mick and I didn’t have bottles or any other supplies for something so helpless.

“Hey,” I whispered sharply, kicking my brother awake again. “You got a diaper bag or something in the car?”

Ollie shrugged, like he was still some surly teenager instead of a forty-two-year-old drunk. Outside the front window, through the falling ice, I saw a gray Ford Taurus with a long, vertical dent in the front fender, as if someone had hit a tree or a pylon. Ollie hated American cars, so now I was curious about the other ways my brother had changed in the last twelve months.

He’d disappeared a year earlier, after Mick beat poor Ollie into a bloody mess. My husband, back in his army days, dreamed of becoming a mixed martial artist, but when he accidentally killed a fellow soldier during an unsanctioned fight, Uncle Sam’s lawyers kicked him out of the airborne and sent him to jail. Fast forward to last winter, to the night Ollie showed up at our house with a stranger, heckling Mick about his Jane Austen obsession – my husband became a Janeite in prison – and asking if we had any fresh-baked cookies for sale. Mick dagger-eyed that stranger, and that look helped me see inside his mind, where memories played of his unhappy prison days filled with boredom and meanness and the shame of having to shit in front of other men. Mick ended up throwing Ollie onto the gravel driveway and whipping my little brother with the brass-buckle end of his belt, cutting gouges into Ollie’s forehead and piercing the jelly of his left eye, rendering it useless for the rest of his days.

Later that same night, Mick and I screwed like feral cats, clawing and biting each other, and when it was over, my husband sat naked on the edge of the bed, his hard, freckled shoulders still tense with some worry. When I kissed one of the red streaks I’d torn into his skin, he squeezed the fat of my thigh and shook it, maybe lovingly, maybe mockingly. That’s when he said he wasn’t ever going back to jail.

“And if your fuck-head brother tries to mess things up, I’ll tear out his throat. He don’t belong in a society among sensible people.”

Ollie, now a year dumber and sitting on my couch, zipped and unzipped his windbreaker, trying his hardest not to think about Mick sleeping in the bedroom down the hall.

“Whose baby is this?” I asked, still rocking it in my arms. That got Ollie crying again. The floor in the living room sagged, and as I stood there, pretending not to notice my brother’s whimpering, I wondered if those old boards would finally give way, swallowing me and the anonymous child squirming in my arms. They didn’t so I hummed Chantilly Lace – that old fifties tune our father used to sing whenever he was drunk and lonely – which brought up stale memories of our childhood. Ollie and me didn’t know our father had kidnapped us from our mother, or that he didn’t own that trailer deep in the Georgia kudzu. That long ago summer began as grand adventure for my brother and me, running bare foot through hot woods, chucking rocks at the windows of rusty, abandoned automobiles, and exploring each other’s privates in the tall grass while keeping an ear out for grown-ups and rattlesnakes. It was like a holiday with no ending, until that morning Ollie came panting out of the doublewide, hollering that dad was asleep with his eyes open, bleeding like crazy from his wrists.

Here’s what Ollie told me about the baby. Earlier in the evening, an aching heart sent him to the River Club – that poor man’s golf course along the Cumberland – in search of his third ex-wife. In the clubhouse bar, he spotted ex-wife number two slow dancing with his old high school nemesis, Cal Burchett. Ollie’s marriage to Janice or Janet – I never was sure of her name – ended a decade ago, and more than twenty years had passed since his high school days, but the pain of seeing those two unhealed scars intermingling was raw enough to get him drinking again. Ollie swore, sitting on my couch, that he’d been sober for eleven of last year’s twelve months, but I’d learned long ago not to trust a word my brother said.

Cal Burchett co-owned The River Club, and apparently he’d gotten into that recent Cross-fit craze, meaning his forty-two-year-old frame didn’t have my brother’s softness, and after Ollie started throwing gold fish crackers at the dancing couple, Cal threw him out.

“Goldfish?” I asked.

“They were in a bowl on the bar.” Ollie grimaced. “The bartender said they were for everybody, as long as I wasn’t greedy about it.”

“Cal give you that shiner?”

My brother touched his closed left eye and then laughed. “This was Mick’s Christmas gift to me last year. Remember?”

“Jesus.” That mangled socket looked freshly warped. “Go on,” I said.

After The River Club, Ollie boot-scooted into Partner’s, the country-western joint along the by-pass. He didn’t remember much of what happened there. No ex-wives, but some off-color jokes were made – by him, I’m sure – and eventually he was in the parking lot, smelling like Bud Light and piss. In fact, as I sniffed the living room air, I realized the odor still clung to him. From Partner’s, he limped along the by-pass’s shoulder, squinting and bowing his head at on-coming headlights, until he reached the Exxon gas pumps at Nicholson’s Market.

“You walked all the way to Nicholson’s?” I paced in front of the couch, shifting the baby from one arm to the other to keep it quiet. “That’s like two miles.”

Ollie smiled for the first time that evening. He said he enjoyed walking – the law took his license a while back – because it gave him time to watch the stars and contemplate the Universe. My brother had confused dreams of being a philosopher or some sort of spiritual shaman, but he was too lazy or twisted in the head to become a Buddha or even a David Koresh. I remember he didn’t talk much after he found our father’s body. I was too scared to look at the corpse, and the days and nights passed slowly as we huddled alone, in the nothingness of rural Georgia, feeling as if we were stranded on the moon.

“By the time I reached Nicholson’s, it was sleeting. And this is all I got on?” Ollie patted his worksite-stained jeans, his gray Russell sweatshirt and the cheap windbreaker that failed to live up to its name. He’d stood in the icy cold, just beyond the market’s lights, an animal seeking survival through warmth. And there, parked on the side of the market, was an idling Ford Taurus, the steam rising from its tailpipe like an index finger beckoning him closer. The driver and passenger seats were empty, and through the store’s front window, Ollie saw the car’s young owner – a girl no older than nineteen or twenty, he said – browsing the aisles, her arms heavy with cans of ravioli and bags of onion skins.

“I didn’t think it’d be unlocked, but Hell if I didn’t sing Hallelujah when the door clicked open.” My brother closed his eyes, transporting himself back to that fleeting moment of good luck in a life guided by shitty providence. He only meant to sit there a minute or two, warming his trembling hands at the dashboard’s vents, but before his mind could catch up with his body, he’d shifted the car into reverse and sped away.

Ollie, not wishing to tempt fate, didn’t look into the rearview mirror until he’d turned off the Bypass onto Old Farmer’s Road. If he’d done so any sooner, his superstitious religion would have placed a police cruiser behind him, its flashing lights gleaming against the falling ice. But figuring Old Farmers was far enough away for him to safely look back, Ollie glanced in the mirror with the same innocent curiosity as Lot’s wife, prompting the prankster God my brother worshiped to place a sleeping child, buckled into a car seat, into the darkness behind him.

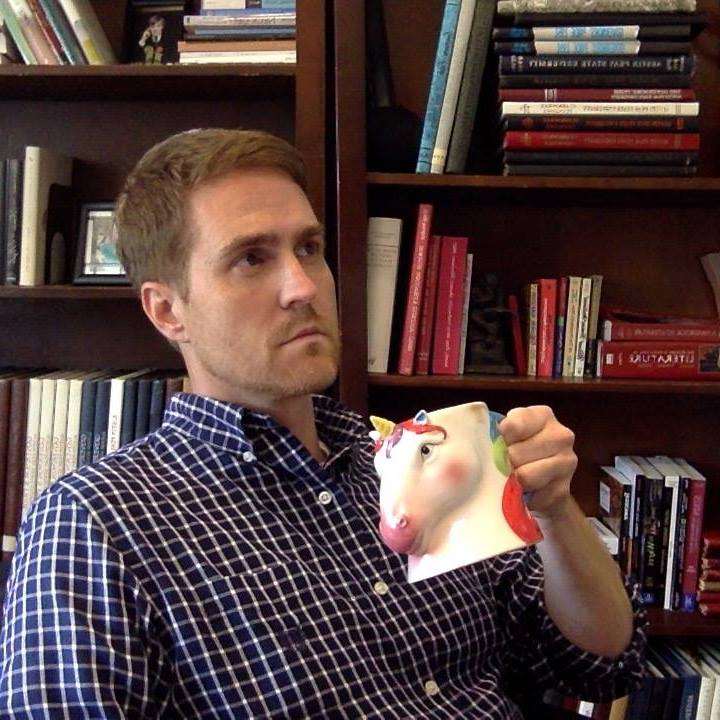

“I was going to dump it in the river.” Ollie now picked up one of Mick’s porcelain teacups decorating our coffee table, examined the rose patterns circumnavigating the dish, and then placed it back on the saucer. “I don’t know why I came here instead.”

“Dump it?

He nodded at me. “The baby. Just get rid of him.”

“You want to kill it?” My own words startled me, causing my muscles to tighten around the child until it whimpered for me to stop. I looked at my brother, trying to find all this unreasonable, but the longer I stood there, examining his mangled eye and gaunt frame, the more I realized I’d do almost anything to protect Ollie from any more hurts.

“You really screwed us all this time.”

The sleet softened to snow, which clung to my Navy pea coat as I ran through the yard. Ollie stayed on the couch, his pinkie stuck in the baby’s mouth to keep it from crying, while I parked the Ford behind the house. We lived out in the county, on a road only used by somber farmers and tweaked Sudafed heads, but if a deputy cruised by, checking the icy roads, he might spot that stolen car and end our little family reunion.

I’d convinced my brother to come with me, in search of nicer, more humane ways of getting rid of a baby, like leaving it inside an unlocked church or on some unsuspecting Samaritan’s doorstep. After parking the Ford, I wrestled with the baby’s car seat, unhooking clamps and trying to jerk it free, but the seat was designed to withstand greater calamities than my brother and me, so I just left it, kicking the door shut and cussing the thing’s tenacity. The car seat battle, along with the cold and the memories of our dad, put me in a foul mood. When I found my brother asleep on the couch, snuggled with the baby, I thumped his bad eye.

“Jesus.” He clamped a free hand to his face, and the sudden movement upset that sleeping baby’s comfort. Its pudgy face creased, in a pre-fit expression, meaning we had to leave now before it woke Mick. I handed my keys to Ollie.

“You OK to drive?”

“I got here, didn’t I?”

He stood, stumbling against the coffee table and rattling the tea set. I looked back through the window, expecting to see the Ford but only finding the tire marks I’d just made in the snow. Still, I remembered the vertical dent in the fender, and as my eyes drifted toward the street, to that darkening region beyond the porch light’s reach, I noticed our mailbox was missing. A splintered wood stump was all that remained of the post that once supported it.

I laughed. “You trying to get yourself killed?”

Ollie didn’t take it as a joke. His quiet, somber expression stung me.

“I’ll drive. You hold that baby tight because I couldn’t get the seat out.”

We ran through the snow toward my little Mazda. A few feet from the passenger door, Ollie hit a patch of ice, losing his footing and ending up on his ass. The baby fell with him, landing safely on my brother’s chest, but then it slid into the snow. The frothy slush clinging to his face pissed that child off good, and he started hollering like one of those old-time police sirens, the screams rising and falling, rising and falling.

Inside the car, Ollie dried the baby’s face, kissed its forehead, and then rocked it against his chest, rubbing its back softly. The little one’s shrieks curled my spine, but my brother was patient with the infant, telling it in a dopey kindergarten teacher voice that everything was ok, he didn’t need to make a fuss.

“If we can’t find a good place to drop him,” Ollie said, smoothing the child’s hair, “I still say we dump it in the river.”

“We’ll cross that bridge later.” I turned the heat to full blast and pointed the vents at Ollie and the baby.

The Mazda moved smoothly through fresh snow, crunching against the deeper drifts where the driveway dipped down. At the edge of our yard, the headlights revealed the corpse-like figure of our mailbox, a dusting of snow covering the gray metal, along with Mick’s and my last name and the random numbers that set our place in this world. Down in the ditch, scattered across a murky puddle crusted with a thin layer of ice, was our mail. The white envelopes and junk coupon books were curled with wetness. A little farther up the ditch, I spotted a banged up cardboard box, and when I saw its contents spilling out of the top, exposed to that bad weather, I thought maybe Ollie and I should just keep on driving that night, with or without the baby, just head some place far like Maine or, at the very least, Northern Kentucky, where Mick couldn’t find us. There, in the frozen muck, was the green and gilded Peacock Edition of “Pride and Prejudice,” a delivery my husband had been waiting on for weeks, hurrying to the mailbox whenever he saw the postal truck pass.

The Mazda fishtailed on Old Farmers as I sped away from the house. The shrieking baby provided the pathetic soundtrack to our adventure. It kept me from talking, though those annoying screeches intensified my foulness, and I drove with hunched shoulders, thinking of all the shit my brother was causing and wondering why oh why was I dead set on loving and protecting the little bastard.

The car slid on a few patches of ice, bringing us dangerously close to ditches and metal guardrails before I corrected everything and got it back under control. Ollie stuck his finger back in the kid’s mouth, which quieted it for a bit, and in that welcome silence, he asked where the hell we were going.

“Nicholson’s,” I said.

“You turning me?”

I thumped that bad eye again and scolded him for not trusting me.

“You’re my brother, even if you are a fuck-up. Don’t you ever doubt that I won’t look out for you.” Even as I said it, I knew my track record didn’t support my claims, which probably helped keep me in such a pissy mood. “I’m just driving by the market. If the cops are there, we can head on. But if not, if she’s still in the store trying to figure out what to do, then maybe we just hand her back junior and get the hell out of there.”

“Why would she still be there?”

“Did you check her car?” I reached into my pea coat while he stared at me and pulled out a baggie of white crystals.

“Jesus Fran. Let’s toss the kid, take that back home and have us a nice time. What do you say?”

Being an older sis was something I never grew comfortable with. Over the years, I’d worked tons of shitty jobs and learned the world was full of folks who loved telling others what to do. For some reason, I’d never been comfortable with that. It’s not because of some moral superiority, but just an aversion to sounding stuck-up and pious. There were plenty of times in my life when I should have counseled Ollie on his decisions, pointed him in the right path, but I always became self-conscious about delivering lectures. Inside my warm Mazda, the stale air of cigarettes and air freshener lingering with us, I should have warned him about the dangers of snorting crank and killing babies, but I simply rolled my eyes, and said for him to hold his goddamn horses.

“If they catch us with that shit,” Ollie nodded at the baggie now wedged between my crotch and the seat, “it won’t look good. Not good at all.”

Before I could answer, I stomped on the brakes. The car must have hit a slick of ice because it didn’t follow my commands. We slid, spinning on that blacktop while I struggled with the steering wheel, jerking it left and right. Finally, with a heavy thump, we hit an embankment, bringing the swirling world to a sudden stop. In the quiet that followed, I pressed the gas, but the Mazda’s tires simply spun in place, kicking up snow and ice and mud.

When I finally resigned myself to being stuck, letting the gas pedal rest a moment, I looked at Ollie and saw he no longer held a baby. My brother sobbed while eying the dark beneath the dash board, and as my sight adjusted, I made out a small, motionless lump, bundled in a brown afghan.

“I tried to hold on to him.” My brother shook his head.

I touched Ollie’s whiskered cheek, but it felt as if my hand had to travel a long way, over a dark and quiet ocean, to reach him. We sat there, me looking at the lump and Ollie avoiding it, Ollie crying out to God that he was sorry for all those he’d hurt. He rubbed his nose on his windbreaker and turned to me. “I really didn’t want to hurt it, Fran. I swear.”

The snow stopped, but an ugly wind blew specks in our raw faces as we stomped away from the Mazda. Just being around Ollie had scrambled my own brain, and at a yellow sign, warning of bridges icing over before roads, I paused and looked back at the car. My car. Whoever found it would discover the child inside, and then our troubles would pile up. The wind stopped for a moment, and the crystal silence helped clear my thoughts.

“Leave it,” Ollie shouted as I ran back to the Mazda. Near the passenger door, my legs sank into snow up to my knees. I hesitated, not wanting to feel the stiff, cold thing beneath that blanket. In that moment, I remembered huddling in the woods with Ollie, holding his thin body while he blinked slowly, as if he were about to drift off into that eternal sleep.

“Eat this,” I’d said, handing him a strip of gray meat. He sniffed it, then jerked his head away. Our instincts are smarter than our brains, but I figured we needed protein, so I’d hacked up that rotting possum for us to eat. Ollie vomited first, curling into a ball to better hold his bile-stained stomach.

“Are we going to die?” He looked at me, disappointed that I wasn’t some angel.

Now, I inhaled the night air and opened the car’s door. The bundle remained on the floor, but when I lifted it, letting the icy night ruffle the afghan, the blanket moved and squealed.

“It’s alive,” I yelled.

Ollie pumped his fist, like his team had just won the Sugar Bowl, and then he ran back to us, putting his arm around me so our two bodies could block the little one from the harsh wind. Our feet squeaked through drifts of snow. We stayed away from the road, so no passing motorists would see us and offer help, but that didn’t matter because no one was stupid enough to be out in that weather.

On the front porch, we stomped snow from our shoes and shook it off our coats. Ollie held the door for me and the baby, and when I walked back to the kitchen, I noticed the new “Pride and Prejudice” splayed open on the counter so its wrinkled pages could dry. Before I could react to this, there came a thump and crash from the living room. The noise upset the baby, prompting him to squirm and scream in my arms. I held him, as if he were a shield, and through the doorway, I saw Ollie pressing two bloody hands over his nose, running back out into the night. Mick, shirtless and with his graying brown hair sticking up from sleep, slammed the door shut and locked it.

“I don’t give second warnings.” He stood with his back to me. “But I’ll do it this time. Your brother comes back here, I’m stomping his guts out.”

“OK.” I didn’t know if he heard me over the baby’s crying. The noise sounded strange in our house, as if we were parents raising our own little one.

“That’s the missing baby?” Mick asked.

“We tried to get rid of it.” The little one moved angrily, but the noise no longer troubled me. When Mick turned and walked toward us, I felt a panic I didn’t want to name. “How do you know about it?”

He nodded toward the television, which was muted. The screen showed a bunch of cop cars at Nicholson’s. I watched the news, wondering if they mentioned my brother’s name or said anything about the Mazda sitting alone on the side of the road. Mick walked past me and out the back door, leaving it open. The cold air bit at me, and I wondered how he could be out there without shoes or a shirt.

“Be quiet now,” I whispered, rocking the baby. “Shhh.”

My husband returned with fresh flakes of snow in his hair, his chest and arms red from the cold. He carried a diaper bag to the counter, opened it and rifled around until he found a round canister of baby formula and some bottles. Mick read the directions slowly, counting out scoops of powder and pouring water into the clear sacks. Then he shook the bottle and motioned for me to hand him the baby.

Even before the little one saw the nipple, it seemed to calm down in his bare arms. Mick sat in his recliner, feeding the baby its bottle, which it sucked at greedily. My husband sniffed the putrid air coming from his lap.

“You fuckers didn’t even think to change its diaper.” He shook his head. “Goddamn.”

Later, when the baby was full and clean and resting in my husband’s arms, I asked what we were going to do. He told me to whisper so I wouldn’t wake the child. Then he said he’d get someone to take it back to its momma. Someone he trusted a hell of a lot more than Ollie and me. While the baby slept, Mick picked up his “Pride and Prejudice” and, as if I wasn’t there, he began to read to this little one about poor, miserable Elizabeth.

“‘When you have killed all your own birds, Mr. Bingley,’ said her mother, ‘I beg you will come here, and shoot as many as you please, on Mr. Bennet’s manor. I am sure he will be vastly happy to oblige you, and will save all the best covies for you.’”

Mick continued with the novel, and while he spoke, I looked at the wood floors, where droplets of my brother’s blood had dried, and I experienced a strange pleasure at the memory of that violence.