I finished Maxim Loskutoff’s latest novel, Old King, on September 1 — twenty-six days before Hurricane Helene tore through Western North Carolina, decimating the region and my community in Asheville.

Loskutoff and I had been exchanging emails for this Q&A throughout that month. The conversation ended abruptly once my entire city and our neighboring counties were closed off to the outside world — no cell phone service, no internet, no electricity, no running water, no safe roadways.

In short, we were living in the type of environment that at least one character in Loskutoff’s novel — Ted Kacynski, better known today as the Unabomber — aspired to find when he left academia and relocated to his infamous cabin in rural Montana in the 1970s to escape the modern world. When his plan was derailed by encroaching development, he ultimately lashed out against society and its evolving technologies through handmade letter bombs.

Of course, Old King is not a mere retelling of Kacynski’s isolation and descent into madness. In fact, much of the novel focuses on characters adjacent to but not directly involved with the Unabomber — be it neighbors within the rural Montana community or the novel’s short vignettes exploring the lives of some of Kacynski’s victims.

On September 1, I shared a photo of Loskutoff’s novel on Instagram and penned a brief post about it. In my final line, I wrote: “If this book were a drink, it’d be the last beer in the fridge, consumed alone, as you watched storm clouds roll in over the mountains.”

It’s still an apt description, given the haunting loneliness that marks most of the novel’s characters — from Duane Oshun, who leaves his young son and ex-wife behind in Salt Lake City, to Kacynski himself. But in the aftermath of Helene, the reference to storm clouds hit in a different way.

Residents in Western North Carolina are still in the midst of processing the utter ruin Helene has brought. Lives were lost, homes destroyed, entire towns washed away. In Asheville, the River Arts District was one of the hardest hit areas. Prior to the storm, this section of town had been home to hundreds of artists. Today, the majority of RAD studios are unrecognizable or completely destroyed. If you have the means, please consider donating to riverartsdistrict.com.

Now, my interview with Loskutoff.

THOMAS CALDER: One of many things that struck me about this book is the way you managed Ted Kaczynski as a character. I could imagine another version of a similar story in which, because of Kaczynski’s notoriety, he is front and center throughout. But you intentionally keep him off the page in the early sections of the book. Speak to me about this decision. Was it a choice you made from the start, or one that arrived in a subsequent draft?

MAXIM LOSKUTOFF: From the start, I saw Kaczynski as a shadow over the Blackfoot Valley. A spectre, a haunting presence rising with the tide of technological dominion in the final third of the twentieth century. There’s actually more of him in the book than there was in earlier drafts. At first, the reader was never inside his head, just glimpsing him through the eyes of other characters.

I didn’t want to make him a hero, or anti-hero, so it was important for me to establish the other people in the valley first. Duane in particular who has a naive optimism, an innocent love for technology as represented by his prized microwave, in contrast to Kaczynski’s hatred.

I had no interest in writing a book ‘inside the mind of a killer.’ Rather I was fascinated by how a community exists with this darkness in its midst for over twenty years. Particularly Kaczynski’s closest neighbors, like Duane, but spreading outward to everyone, even those who never meet him, but are impacted by his presence. In the modern world we’re all afraid of killers we’ve never met, people we’ve never seen, so I found this kind of haunting to be an inverse of our experience. What if the violence really did live invisibly next door?

CALDER: I’m very happy you initiated the conversation about the S-Series Touchmatic microwave. The novel’s opening section begins with Duane reclaiming (i.e., stealing) the kitchen appliance from his ex-wife. There’s something delightfully petty about the act. But it takes on such a deeper meaning as the novel progresses. Talk to me about this specific object. Was it present in the initial draft? Or did it appear later, once you better understood the issues you were interested in exploring in this novel?

LOSKUTOFF: Strangely, it was present from the very first scene in the very first draft. I knew I wanted to write a novel in which the theme of nature vs. technology plays out in a small, remote community, but words didn’t appear on the page until Duane began to form in my mind. I felt that his own dream of living alone in the wild would play out in contrast to Kacynski’s, and his desperate attempt to reclaim some piece of his life from his ex-wife before he flees was my introduction to him as a character. I was surprised that it turned out to be a microwave. I think it came from the fact that to my childhood self, microwaves were the most quietly miraculous appliance in most homes. This little plastic box that existed outside the bounds of what I considered reality, and could somehow cook food from frozen in mere minutes. For someone like Duane, who retains the naive optimism of post-WWII, it represents all the possibilities of America, and the possibilities he wants for his own life.

CALDER: I love knowing the microwave was there from the start. You’ve mentioned in both responses your interest in writing on nature vs. technology. Was this theme what led you to Kacynski or has Kacynski’s story been a source of fascination that led you to exploring these themes?

LOSKUTOFF: I think my fascination crystallized around Kaczynski because I hadn’t thought of the two in opposition before. I was 11 when he was caught, which is around the age you stop accepting things as they are. For a while when you’re a kid, the world is just the world. Your town your town, your parents your parents, etc. Then you start making distinctions, wishing things were different. A bigger house, a nicer bike, less clearcuts, more wolves. In Kacynski, and all the media madness surrounding his capture, I discovered that there was a faction of people who saw technology as outside of nature. Outside the natural order of things, and our place within it as human beings. I spent the next couple decades chewing on that, trying to figure it out.

CALDER: Along with nature v. technology, your novel also explores the individual v. the community. There seems to be a shared tension within many of the book’s characters who strive to get away and create their own place in the world but cannot completely divorce themselves from the need for connection — be it through wildlife or romantic partners or in a very odd way Kaczynski’s deranged link to the outside world through his violent acts.

As you were creating this world of characters, how were you thinking about this dynamic — privacy v. company.

LOSKUTOFF: For me, that’s one of the tragedies at the core of the whole frontier dream: this idea of a man alone in the wilderness. Coming into wild country and taming a piece for himself, self-reliant, self-sufficient. As if that was ever something to be venerated. Certainly in ancient and indigenous cultures people went off alone for a time, for spiritual rituals or rites of passage, but this idea of living that way permanently, as something to aspire to?

America was born around the same time as Individualism, and it became a proving ground for many of its principles. By the 1970s there was a growing sense that something was wrong, in the burgeoning environmental movement in particular, but the heart of the problem still remained. So Old King is for me a book about three men with very different ambitions who all make the same mistake — trying to make it on their own — while the answer to their suffering would be a true sense of community, support, respect, a sense of purpose, of being loved and a part of something greater. Those moments of connection you mention, that push and pull … I think we all feel alone here in the west, in a deeper sense, so while it’s a novel about a community, Lincoln, it’s really about how these neighbors live in close proximity but don’t really know each other at all.

CALDER: This seems like a good spot to talk about one of the novel’s other key characters — Jackie. She might be my favorite of the bunch. For readers who’ve yet to read the book, Jackie works at the Ponderosa Cafe. She was previously married to one of the story’s main characters, Mason, though the pair is separated by the time we meet her. And she ends up dating Duane, who is a decade younger than her. She also basically knows most everyone in town, except maybe Kaczynski? Regardless, she’s a central figure within the community.

I wanted to share an exchange that I love from the novel (on page 82) and get your thoughts on it, as well as hear more from you about Jackie as a character. Old King is full of idealistic and often destructive men, which makes Jackie — one of the book’s few female characters — stick out even more, in that she seems somehow above the existential threats and dread they face/create. She has her sadness, but she also seems oddly at peace in many ways.

Here’s the excerpt:

“I think people need to cut down trees to put roofs over their heads, just like they need to hunt animals to eat. There’s just too damn many people these days. If it were up to me, I’d rip out the highway and make them come on horseback like they used to. Then they could leave these mountains alone.” She paused, feeling Duane’s eyes searching her. “When I was a girl, it was all miners in Lincoln, then the lumber mill opened and it was all loggers, now it’s mostly tourists. I don’t know what will come next.”

“So you don’t think it’s bad?” Again Jackie saw in Duane the lost boy trying to make sense of the world.

“No, I don’t think it’s bad,” she answered. “I used to, and Mason and some others do, but now I see it as people just trying to get by. If you don’t cut wood, someone’s going to be cold, and if you don’t want a lot of people freezing to death or going hungry, that’s the way it is. Everyone thinks they deserve a comfortable life. And maybe they do.” Jackie knelt and opened the cupboard by the stove, searching for sugar. She was surprised by her own soliloquy; it was different than what she would’ve said five years before. When she was married to Mason, she’d believed that every remaining acre of wild forest in Montana should be protected, and the punishment for killing an endangered animal should be the same as for killing a person.

LOSKUTOFF: Yes, Jackie represents a layer of wisdom deeper than the men in the book. The three main male characters — Duane, Mason, and Kaczynski — all come to Lincoln wanting something from the wild. Mason wants to save it, Duane wants to be saved by it, and Kaczynski wants to use it as the foil for the society he hates. They’re all trapped in the binary of man over here, and wilderness over there, as separate entities. Jackie was born in the Blackfoot Valley and is a part of the natural world in a way the men aspire to be, and even fall in love with, but can never quite attain, save in fleeting moments. Her understanding of the reality of existence is operating on a deeper level. She knows we can never be apart from nature, and she understands that we aren’t actually individuals, we’re relationships. Our bodies are entire planets unto themselves, supporting worlds of bacteria, just as earth supports the many threads of our ecosystem.

Her patience with mankind’s destructive tendencies comes from a hard-earned wisdom about our nature. We are terraformers, we transform landscapes, clear fields, build homes, all out of love for the ecosystems of our families and our own bodies. So the way forward isn’t to deny those tendencies–deny that the freezing man needs shelter from the storm–but to incorporate them into a broader sense of stewardship. One based on relationships, the true nature of existence, rather than accumulation. This understanding made her in a sense the heart of the book. The only one who weathers these 25 years in the Blackfoot Valley.

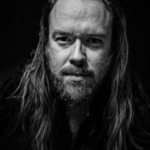

MAXIM LOSKUTOFF was raised in the Rocky Mountains of western Montana. He published his first story at nineteen and his debut collection COME WEST AND SEE won the High Plains Book Award, was a NY Times Editor’s Choice, and an NPR and Amazon Best Book of 2018. “A new kind of American western.” (NPR) His debut novel RUTHIE FEAR won the Montana Innovation Award and the High Plains Book Award in 2021, received starred reviews from Kirkus, PW, and Booklist, and was a Reading the West Award Finalist. “Astonishing…a magnificent novel.” (Bookreporter) His second novel OLD KING, “eerily atmospheric, keep-you-up-late suspenseful” (SF Chronicle), was published in June 2024 and named a Best Book of Summer by the Boston Globe and Minneapolis Star Tribune, and a Best Book of the Year by PW. “Loskutoff is unmatched at evoking the contentious, transitional nature of the American West.” (WSJ) The recipient of fellowships from Yaddo and MacDowell, his writing has appeared in the NY Times, Chicago Tribune, Ploughshares, GQ, and many other magazines. He is currently the Visiting Writer in the MFA Program at the University of Montana.

MAXIM LOSKUTOFF was raised in the Rocky Mountains of western Montana. He published his first story at nineteen and his debut collection COME WEST AND SEE won the High Plains Book Award, was a NY Times Editor’s Choice, and an NPR and Amazon Best Book of 2018. “A new kind of American western.” (NPR) His debut novel RUTHIE FEAR won the Montana Innovation Award and the High Plains Book Award in 2021, received starred reviews from Kirkus, PW, and Booklist, and was a Reading the West Award Finalist. “Astonishing…a magnificent novel.” (Bookreporter) His second novel OLD KING, “eerily atmospheric, keep-you-up-late suspenseful” (SF Chronicle), was published in June 2024 and named a Best Book of Summer by the Boston Globe and Minneapolis Star Tribune, and a Best Book of the Year by PW. “Loskutoff is unmatched at evoking the contentious, transitional nature of the American West.” (WSJ) The recipient of fellowships from Yaddo and MacDowell, his writing has appeared in the NY Times, Chicago Tribune, Ploughshares, GQ, and many other magazines. He is currently the Visiting Writer in the MFA Program at the University of Montana.